Cancer Research Moves Forward by Fits and Starts

May 7, 2015 Leave a comment

![]() I recently returned from the American Association for Cancer Research (AACR) meeting held in Philadelphia. AACR is attended by basic researchers focused on the molecular basis of oncology. Many of the concepts reported will percolate to the clinical literature over the coming years.

I recently returned from the American Association for Cancer Research (AACR) meeting held in Philadelphia. AACR is attended by basic researchers focused on the molecular basis of oncology. Many of the concepts reported will percolate to the clinical literature over the coming years.

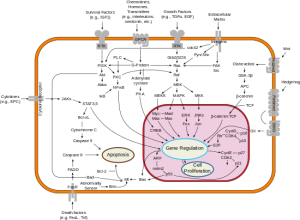

There were many themes including the revolution in immunologic therapy that took center stage, as James Allison, PhD, received the Pezcoller Prize for his groundbreaking work in targeting immune checkpoints. The Princess Takamatsu Award given to Dr. Lewis Cantley, recognized his seminal contribution to our understanding of signal transduction at the level of PI3K. A series of very informative lectures were provided on “liquid biopsies” that examine blood, serum and other bodily fluids to characterize the process of carcinogenesis. These technologies have the potential to revolutionize the diagnosis and monitoring of cancers.

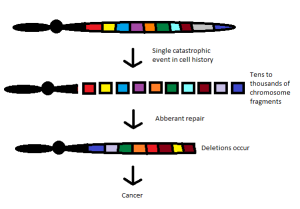

The first symposium I attended described the phenomenon of chromothripsis. This represents a catastrophic cellular trauma that results in the simultaneous fragmentation of chromosomal regions, allowing for rejoining of disparate chromosome components, often leading to malignancy and other diseases. I find the concept intriguing, as it reflects the intersection of oncology with evolutionary developmental biology, reminiscent of the outstanding work of Stephen Jay Gould. His theory of punctuated equilibrium, from 1972, challenged many long held beliefs in the study of evolution.

Since the time of Charles Darwin, we believed that evolution was slow and continual. New attributes were selected under environmental pressure and the population carried those characteristics forward toward higher complexity. Gould and his associate, Niles Eldredge, stated that evolution was anything but gradual. Indeed, according to their hypothesis, evolution occurred as a state of relative stability, followed by brief episodes of disruption. This came to mind as I contemplated the implications of chromothripsis.

According to the new thinking (chromothripsis and its related fields), cancer may arise as a single cell forced to recover from what would otherwise be catastrophic injury. The reconfiguring of genetic elements scrambled together to avoid apoptosis (programmed cell death) provides an entirely new biology that can progress to full-blown malignancy.

By this reasoning, each patient’s cancer is unique. The results of damage control whereby chromosomal material is rejoined haphazardly would be largely unpredictable. These cancers would have a fingerprint all their own, depending on which chromosome was disrupted.

As high throughput technologies and next generation sequences continue to unravel the complexity of human cancer, we seem to be more and more like those who practice stone rubbing to create facsimiles of reality from the “surface” of our genetic information. Like stone rubbing, practitioners do not create the images, but simply borrow from them.

With each symposium, we learn that cancer biology does not come to be, but is. Grasping the complexity of cancer requires the next level of depth. That level of depth is slowly being recognized by investigators from Harvard University to Vanderbilt as the measurement of humor tumor phenotypes.

Cancer is phenotypic and human biology is phenotypic. Laboratory analyses that allow us to measure, grasp, and manipulate phenotypes are those that will provide the best outcomes for patients. Laboratory analyses like the EVA-PCD.