Is Cancer a Genetic Disease?

April 13, 2015 Leave a comment

I recently had the opportunity to meet two charming young patients: One, a 32-year-old female with an extremely rare malignancy that arose in her kidney and the other a 33-year-old gentleman with widely metastatic sarcoma.

Both patients had obtained expert opinions from renowned cancer specialists and both had undergone aggressive multi-modality therapies including chemotherapy, radiation and surgery. Although they suffered significant toxicities, both of their diseases had progressed unabated. Each arrived at my laboratory seeking assistance for the selection of effective treatment.

With the profusion of genomic analyses available today at virtually every medical center, it came as no surprise that both patients had undergone genetic profiling. What struck me were the results. The young woman had “no measurable genetic aberrancies” from a panoply of 370 cancer-causing exomes, while the young man’s tumor revealed no somatic mutations and only two germ-line SNV’s (single nucleotide variants) from a 50 gene NextGen sequence, neither of which had any clinical or therapeutic significance.

With the profusion of genomic analyses available today at virtually every medical center, it came as no surprise that both patients had undergone genetic profiling. What struck me were the results. The young woman had “no measurable genetic aberrancies” from a panoply of 370 cancer-causing exomes, while the young man’s tumor revealed no somatic mutations and only two germ-line SNV’s (single nucleotide variants) from a 50 gene NextGen sequence, neither of which had any clinical or therapeutic significance.

What are we to make of these findings? By conventional wisdom, cancer is a genetic disease. Yet, neither of these patients carried detectable “driver” mutations. Are we to conclude that the tumors that invaded the cervical vertebra of the young woman, requiring an emergency spinal fusion, or the large mass in the lung of the young man are not “cancers”? It would seem that if we apply contemporary dogma, these patients do not have a cancer at all. But nothing could be further from the truth.

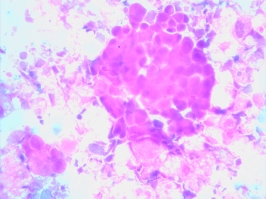

Cancer as a disease is not a genomic phenomenon. It is a phenotypic one. As such, it is extremely likely that these patients’ tumors are successfully exploiting normal genes in abnormal ways. The small interfering RNAs or methylations or acetylation or non-coding DNA’s that conspired to create these monstrous problems are too deeply encrypted to be easily deciphered by our DNA methodologies. These changes are effectively gumming up the works of the cancer cell’s biology without leaving a fingerprint.

I have long recognized that cellular studies like the EVA-PCD platform provide the answers, through functional profiling, that genetic analyses can only hope to detect. The assay did identify drugs active in these patients’ tumor, which will offer meaningful benefit, despite the utter lack of genetic targets. Once again, we are educated by cellular biology in the absence of genomic insights. This leaves us with a question however – is cancer a genetic disease?