Is There a Role for PI3k Inhibitors in Breast Cancer? Maybe.

March 20, 2015 2 Comments

Over the past decades oncologists have learned that cancer is driven by circuits known as signal transduction pathways.  The first breakthroughs were in chronic myelogenous leukemia (CML) where a short circuit in the gene as c-Abl caused the overgrowth of malignant blasts. The development of Imatinib (Gleevec) a c-Abl inhibitor yielded brilliant responses and durable remissions with a pill a day.

The first breakthroughs were in chronic myelogenous leukemia (CML) where a short circuit in the gene as c-Abl caused the overgrowth of malignant blasts. The development of Imatinib (Gleevec) a c-Abl inhibitor yielded brilliant responses and durable remissions with a pill a day.

The next breakthrough came with the epidermal growth factor pathway and the development of Gefitinib (Iressa) and shortly thereafter Erlotinib (Tarceva). Good responses in lung cancers, many durable were observed and the field of targeted therapy seemed to be upon us.

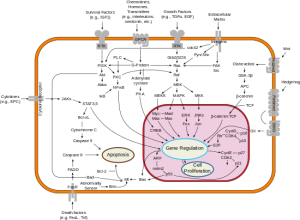

Among the other signal pathways that captured the imagination of the pharmaceutical industry as a potential target was phospho-inositol-kinase (PI3K). Following experimental work by Lew Cantley, PhD, who first described this pathway in 1992, more than a dozen small molecules were developed to inhibit this cell signal system.

Among the other signal pathways that captured the imagination of the pharmaceutical industry as a potential target was phospho-inositol-kinase (PI3K). Following experimental work by Lew Cantley, PhD, who first described this pathway in 1992, more than a dozen small molecules were developed to inhibit this cell signal system.

The PI3K pathway is important for cell survival and regulates metabolic activities like glucose uptake and protein synthesis. It is associated with insulin signaling and many bio-energetic phenomena. The earliest inhibitors functioned downstream at a protein known as mTOR, and two have been approved for breast, neuroendocrine and kidney cancers. Based on these early successes, PI3K, which functions upstream and seemed to have much broader appeal, became a favored target for developmental clinical trials.

The San Antonio Breast Cancer Symposium is one of the most important forums for breast cancer research. The December 2014 meeting featured a study that combined one of the most potent PI3K inhibitors, known as Pictilisib, with a standard anti-estrogen drug, Fulvestrant, in women with recurrent breast cancer. The FERGI Trial only included ER positive patients who had failed prior treatment with an aromatase inhibitor (Aromasin, Arimidex or Femara). The patients were randomized to receive the ER blocker Fulvestrant with or without Pictilisib.

With seventeen months of follow-up there was some improvement in time to progressive disease, but this was not large enough to achieve significance and the benefit remains unproven. A subset analysis did find that for patients who were both ER (+) and PR (+) a significant improvement did occur. The ER & PR (+) patients benefitted for 7.4 months on the combination while those on single agent Fulvestrant for only for 3.7 months.

The FERGI trial is more interesting for what it did not show. And that is that patients who carried the PI3K mutation, the target of Pictilisib, did not do better than those without mutation (known as wild type). To the dismay of those who tout the use of genomic biomarkers like PI3K mutation for patient drug selection, the stunning failure to identify responders at a genetic level should send a chill down the spine of every investor who has lavished money upon the current generation of genetic testing companies.

It should also raise concerns for the new federal programs that have designated hundreds of millions of dollars on the new “Personalized Cancer Therapy Initiatives” based entirely on genomic analyses. The contemporary concept of personalized cancer care is explicitly predicated upon the belief that genomic patient selection will improve response rates, reduce costs and limit exposure to toxic drugs in patients unlikely to respond.

This unanticipated failure is only the most recent reminder that genomic analyses can only suggest the likelihood of response and are not determinants of clinical outcome even in the most enriched and carefully selected individuals. It is evident from these findings that PI3K mutation alone doesn’t define the many bioenergetic pathways associated with the phenotype. This strongly supports phenotypic analyses like EVA-PCD as better predictors of response to agents of this type, as we have shown in preclinical and clinical analyses.

A few weeks ago, a story was published about a terminal colorectal cancer patient who went into remission after receiving a drug based on genomic analysis of her tumor. However, her oncologist, Dr. Howard Lim, was quoted to the effect that “in most cases genomic testing reveals that standard chemotherapy drugs are the best option”:

http://www.ctvnews.ca/health/pill-that-sent-cancer-into-remission-may-be-a-one-off-doc-says-1.2276290

If true, would this observation apply also to phenotypic-functional testing such as “EVA-PCD”?

Dear Shaker,

The quote from Dr Lim excerpted from the link is provided: “But in most cases, he says, genomic testing reveals that standard chemotherapy drugs are the best option. ”

I have several comments before I answer your specific question.

First, those commercial entities and academic centers that have promoted genomic analysis to predict response to chemotherapy have been singularly unsuccessful as was very elegantly reviewed at a special symposium at ASCO in 2014 by Dr. Jean-Charles Soria, MD, PhD from Institut Gustav Roussy in Paris. He meticulously reviewed the data and found no evidence that these gene-based platforms predicted response.

Second, the more legitimate groups like Foundation, have expressly avoided chemotherapy drug selection and use exome screening to identify putative driver gene mutations for select cancers. There is a growing recognition however, that despite the commercial success of many of these groups, most of the mutations identified are either “non-drivers” or “un-druggable”, leaving patients with no actionable advice.

In this context, Dr. Lim’s quote seems hard to address. Does he mean that the cytotoxic drugs would be the same? In which case I would not be at all surprised that an ineffective methodology does not bring much to the table. Alternatively does he mean that the gene mutations reveal no actionable findings and one must fall back onto conventional chemotherapy? This seems more likely, as these results often provide unexpected findings that serve as curiosities that most doctors cannot utilize.

Now to your question. The answer is a resounding No! Phenotypic analyses like EVA/PCD provide the actual biology of each patients cancer in real time. It is the downstream result of cytotoxic injury, growth factor withdrawal or other stress. Both conventional chemotherapy and targeted drugs can be studied. As there is no human cancer for which there is just one therapy, the accuracy of the EVA/PCD platform has been well established in every study we have published.

One need only review the results of our 2012 Lung Cancer paper to see that patients responded a wide variety of therapies (both cytotoxic and targeted) that were identified and used, resulting in a clear doubling of the objective response rate (64.5%, p = 0.0015) and near doubling of survival from 13.5 to 21.3 months.