Chemosensitivity Testing – What It Is and What It Isn’t

July 1, 2015 Leave a comment

Several weeks ago I was consulted by a young man regarding the management of his heavily pre-treated, widely metastatic rectal carcinoma. Upon review of his records, it was evident that under the care of both community and academic oncologists he had already received most of the active drugs for his diagnosis. Although his liver involvement could easily provide tissue for analysis, I discouraged his pursuit of an ex vivo analysis of programmed cell death (EVA-PCD) assay. Despite this, he and his wife continued to pursue the option.

As I sat across from the patient, with his complicated treatment history in hand, I was forced to admit that he looked the picture of health. Wearing a pork pie hat rakishly tilted over his forehead, I could see few outward signs of the disease that ravaged his body. After a lengthy give and take, I offered to submit his CT scans to our gastrointestinal surgeon for his opinion on the ease with which a biopsy could be obtained. I then dropped a note to the patient’s local oncologist, an accomplished physician who I respected and admired for his practicality and patient advocacy.

A week later, I received a call from the patient’s physician. Though cordial, he was puzzled by my willingness to pursue a biopsy on this heavily treated individual. I explained to him that I was actually not highly motivated to pursue this biopsy, but instead had responded to the patient’s urging me to consider the option of performing an EVA-PCD assay. I agreed with the physician that the conventional therapy options were limited but noted that several available drugs might yet have a role in his management including signal transduction inhibitors.

I further explained that some patients develop a process of collateral sensitivity, whereby resistance to one class of drugs (platins, for example) can enhance the efficacy of other class of drugs (such as, antimetabolite) Furthermore, patients may fail a drug, then be treated with several other classes of agents, only then a year of two later, manifest sensitivity to the original drug.

Our conversation then took a surprising turn. First, he told me of his attendance at a dinner meeting, some 25 years earlier, where Dan Von Hoff, MD, had described his experiences with the clonogenic assay. He went on to tell me how that technique had been proven unsuccessful finding a very limited role in the elimination of “inactive” drugs with no capacity to identify “active” drugs. He finished by explaining that these shortcomings were the reason why our studies would be unlikely to provide useful information.

Our conversation then took a surprising turn. First, he told me of his attendance at a dinner meeting, some 25 years earlier, where Dan Von Hoff, MD, had described his experiences with the clonogenic assay. He went on to tell me how that technique had been proven unsuccessful finding a very limited role in the elimination of “inactive” drugs with no capacity to identify “active” drugs. He finished by explaining that these shortcomings were the reason why our studies would be unlikely to provide useful information.

I found myself grasping for a handle on the moment. Here was a colleague, and collaborator, who had heard me speak on the topic a dozen times. I had personally intervened and identified active treatments for several of his patients, treatments that he would have never considered without me. He had invited me to speak at his medical center and spoke glowingly of my skills. And yet, he had no real understanding of what I do. It made me pause and wonder whether the patients and physicians with whom I interact on a daily basis understand the principles of our work. For clarity, in particular for those who may be new to my work, I provide a brief overview.

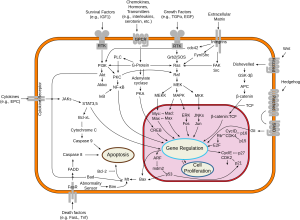

1. Cancer patients are highly individual in their response to chemotherapies. This is why each patient must be tested to select the most effective drug regimen.

2. Today we realize that cancer doesn’t grow too much it dies too little. This is why older growth-based assays didn’t work and why cell-death-based assays do.

3. Cancer must be tested in their native state with the stromal, vascular and inflammatory elements intact. This is why we use microspheroids isolated directly from patients and do not grow or subculture our specimens.

4. Predictions of response are not based on arbitrary drug concentrations but instead reflect the careful calibration of in vitro findings against patient outcomes – the all-important clinical database.

5. We do not conduct drug resistance assays. We conduct drug sensitivity assays. These drug sensitivity assays have been shown statistically significantly to correlate with response, time to progression and survival.

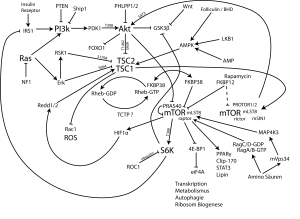

6. We do not conduct genomic analyses for there are no genomic platforms available today that are capable of reproducing the complexity, cross-talk, redundancy or promiscuity of human tumor biology.

7. Tumors manifest plasticity that requires iterative studies. Large biopsies and sometimes multiple biopsies must be done to construct effective treatment programs.

8. With chemotherapy, very often more is not better.

9. New drugs are not always better drugs.

10. And finally, cancer drugs do not know what diseases they were invented for.

While we could continue to enumerate the principles that guide our practice, one of the more important principles is humility. Medicine is a humbling experience and cancer medicine even more so. Patients often know more than their doctors give them credit for. Failing to incorporate a patient’s input, experience and wishes into the treatment programs that we design, limits our capacity to provide them the best outcome.

With regard to my colleague who seemed so utterly unfamiliar with these concepts, indeed for a large swath of the oncologic community as a whole, I am reminded of the saying “There’s none so blind as those who will not see.”

Reposted from March 23, 2012