Of Cells, Proteins and Cancer Drug Development

May 13, 2015 Leave a comment

Our recent presentation at the American Association for Cancer Research meeting reported our work with a novel class of compounds known as the HSP90 inhibitors. AACR 2015-HSP90 Abstract

The field began decades earlier when it was found that certain proteins in cells were required to protect the function of other newly formed proteins hormone receptors and signaling molecules. Estrogen and androgen receptors, among others, require careful attention following their manufacture or they will find themselves in the cellular waste bin.

As each new protein is formed it risks digestion at the hands of a garbage disposal-like device known as a proteasome (named for its protein digesting capabilities). To the rescue comes HSP90 that chaperones these newly created proteins through the cell and protects them until they can assume their important roles in cell function and survival.

As each new protein is formed it risks digestion at the hands of a garbage disposal-like device known as a proteasome (named for its protein digesting capabilities). To the rescue comes HSP90 that chaperones these newly created proteins through the cell and protects them until they can assume their important roles in cell function and survival.

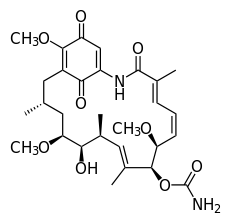

Recognizing that these proteins were critical for cell viability, investigators at Sloan-Kettering and others developed a number of molecules to block HSP90. The original compounds known as ansamycins underwent clinical trials with evidence of activity in some breast cancers. The next generation of compounds was tested in other diseases. Though the clinical results have been mixed, the concept remains attractive.

We compared two drugs of this type and showed that they shared similar function but had different chemical properties and that the concentrations required to kill cells differed. What is interesting is the activity of these drugs seems to be patient-specific. That is, each patient, whether they had breast or lung cancer, showed a unique profile that was not directly connected to the type of cancer they had. This has important implications.

Today, pharmaceutical companies develop drugs by disease type. Compounds enter Phase II trials with 30 to 50 lung cancer patients treated, then 30 to 50 breast cancer patients treated and so on. This continues until (it is hoped) one of the diseases provides a favorable profile and the data is submitted to the FDA for a disease-specific approval. As home runs are rare, most drugs never see the light of day failing to provide sufficient response in any disease to warrant the enormous expense of bringing them to market.

What we found with the HSP90 inhibitors is that some breast cancers are extremely sensitive while others are not. Similarly some lung cancers are extremely sensitive while others are resistant. This forces us once again to confront the fact that cancer patients are unique.

Pharmaceutical companies exploring the role of targeted agents like the HSP90 inhibitors must learn to incorporate patient individuality into the drug development process. Failing to do so not only risks the loss of billions of dollars but more importantly denies patients access to active novel agents.

The future of drug development can be bright if the pharmaceutical industry embraces the concept that each patient’s profile of response is unique and that these responses reflect patient-specific, not diagnosis-based drivers. Clinical trials must incorporate individual patient profiles. Drugs could be made more available once Phase I studies were complete by using biomarkers for response, such as the EVA-PCD assay, which has the capacity to enhance access and streamline drug development.